Winter 2019

Looking Ahead

By Jennifer Harper, Reserve Manager

Hurricane Michael certainly put a damper on our planned programming this past fall with a storm surge of 4-5 feet of water underneath the headquarters. The life support for the aquaria, including the plumbing, filtration, pumps and tanks were all impacted by the surge. Two of the large cisterns that are used to collect rainwater were dislodged from their foundation by the storm as well. We utilize the water from the cisterns to flush our toilets, so we had to bypass the system to use city water. About half of our boardwalk system was lifted out of the ground, much of it in one giant piece, so it may be quite a long time before we are able to rebuild them. After many weeks of picking up, cleaning, and salvaging, we are finally starting to put things back together. Thankfully, most of the building was not impacted and the staff are slowing getting back to their normal duties. The Nature Center has reopened and we look forward to having the tanks back up and running sometime this spring.

One of the activities that was delayed because of the storm was the kick-off meeting for the development of our new management plan. The staff have been brainstorming and gathering their priorities to include in this strategic planning process which happens every five years or so. It really is a good opportunity to think critically about which audiences we want to target, what our capacity is to offer services, and how to build that capacity. Following our planning meeting in January, we will reach out to the Reserve Advisory Committee for their input as we develop our draft. Our goal is to have a draft for review by next fall.

Another big event in 2019 that we are looking forward to is our 40th anniversary. We have already kicked off the planning for the event, which will most likely be held during Estuaries Week in September. Not only is it the 40th anniversary of the Reserve, but also the 30th anniversary of the Friends of the Reserve, 30th anniversary of the designation of the Reserve as a UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve, and the 20th Estuaries Day! It is going to be a special time, and we are looking forward to highlighting all of our successes over the last 40 years, as well as showcasing the productivity and diversity of the system that makes this place so unique and valuable. Look for a Save-the-Date announcement coming out soon.

The Marshall House

By Kim Wren, Stewardship Coordinator

Located on Little St. George Island, a 2,300-acre uninhabited barrier island, the Marshall House is a treasure of local history. This early 1900’s Florida homestead sits on the northern side of the island facing Apalachicola Bay. The Marshall House was constructed by Herbert Marshall for his family to live in while on Cape Saint George Island. His wife, Pearl Porter Marshall, was the daughter of the former Cape Saint George Lighthouse keeper, Edward Gibbs Porter. Edward lived on the island with an assistant and his family, maintained the lighthouse and tended livestock. Most provisions were secured from Apalachicola by the assistant keeper. In the 1890s, Edward purchased the island from Thomas Orman, except for six acres, the lighthouse and two dwellings owned by the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment. Following Edward’s death in 1913, his daughter Pearl, still a child, would return to the island during the summers. Mainland residents would vacation on the island, including the Marshall family, who regularly visited the Porters.

In 1923, Pearl married Herbert Marshall after he returned from service in the Navy. They moved to the island into the former light keeper’s house and would drive cattle from neighboring areas for treatment in one of their three dipping vats on the island. After settling a tax assessment on the Porter holdings, they assumed ownership of the entire island, except for the federally-managed portion. They leased the property to turpentine companies from 1910-1916 and again from 1950-1956. Many “catfaced” scars can still be seen today on the island’s pines as well as remnants from old turpentine camps. During World War II, the island served as a practice gunnery range for B-24 bombers stationed in nearby Apalachicola. The Marshalls eventually relocated mainland when Herbert was employed with the State Road Department. He would then serve for sixteen years as a sheriff for Franklin County.

From the left: Harry Porter, Bess Marshall Porter, Herbert Marshall, Pearl Porter Marshall, “Bunks” Porter, & Mary Virginia Porter in front.

When the Apalachicola Army Air Field closed in 1945, Herbert purchased two Army barracks and create a cottage on the island. The two units, mostly cypress and pine, were modified to create a T-plan structure. The first unit, a large open living/dining room with a central fireplace was joined to the second and divided into two bedrooms with a bathroom in between. After the Coast Guard assumed operation of the lighthouse, the Marshalls were notified the agency intended to raze their former dwelling and Pearl’s childhood home. Herbert claimed the rights to salvage lumber and materials, and would subsequently incorporate the pine flooring and doors into the bay-side residence he constructed. The Marshalls continued to visit the property until a boating accident resulted in Herbert’s death in 1976.

Cape St. George Island was purchased in 1977 under the Environmentally Endangered Lands program to protect it from development and to contribute to the protection of Apalachicola Bay. The island is owned by the State of Florida and managed by the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (ANERR).

Little St. George Island, a remote barrier island, is accessible only by boat and consists of over nine miles of undeveloped beach. It is separated from St. George Island by Sike’s Cut, a man-made pass dredged in 1954, and from Saint Vincent Island by West Pass, a natural inlet into Apalachicola Bay. In the last three years, Reserve Stewardship staff have developed four nature trails and five primitive campsites for all to enjoy. Most roads and trailhead are named and marked with wood signs. Kiosks with educational information were installed at Sike’s Cut, Marshall House dock and West Pass. Interpretive signage detailing the history of the Marshall House and the island were recently placed on the island.

The island’s remoteness and wilderness qualities provide an opportunity to explore a remnant of Florida’s original natural landscape. Historically the homestead was protected by elevation and a large sand dune that blocked the view of the bay. Today, the property has a direct view of the beach from the north. To preserve the facility, staff, along with volunteers and the Forgotten Coast Conservation Corps, installed a 400’ living shoreline consisting of bagged oyster shell and native plants to protect the eroding shoreline. Staff are currently working on minor interior repairs and will continue to apply for grants to conserve, repair and restore this historical homestead.

Estuaries Day

By Gibby Conrad, Education Specialist

Reserve staff spend many hours preparing this annual favorite

Many interactive activities, such as “touch tanks” were available for all to enjoy and explore.

Many interactive activities, such as “touch tanks” were available for all to enjoy and explore.

Estuaries Day 2018 is in the books and was by all accounts a great success. 954 people attended this year’s event with an even 50/50 split of adults and children. When the gates opened at 1:30, attendees lined up to receive their free Estuaries Day t-shirt featuring a brown pelican in flight. Adults also received a ticket to participate in the door prize drawing at the end of the day. Local merchants and businesses were very generous in supplying a wide range of prizes for the drawing.

Activities were spread throughout the campus. The Nature Center was reptile central with a sea turtle hatchling obstacle race, reptile round up game and live snakes, lizards and turtles in the bay discovery room. A new word search game was held on the boardwalk with an “I Love Estuaries” tattoo prize for those who completed the search. Kids were lined up all day at the touch tanks at the foot of the amphitheater where they could see, touch and learn about a wide diversity of marine animals. In the outdoor classroom, Trashy Trivia and Microplastic Match Up focused on the problems of trash in our waterways. A special shout out to Brenda Humphrey, a volunteer who has been assisting the research department in their studies of microplastics on local beaches.

Millender Park was the setting for several favorites like the Wacky Waterfront Race, the Cast Net Game and Small Fry Fishing Game. Debbie Fletcher and the several of her culinary program students from Franklin County High School served refreshments at the Snack Shack again this year. The Gulf Specimen Marine Lab brought their Sea Mobile and several state agencies had displays ranging from black bears to scallops. There was a monarch butterfly tagging demonstration along with a Pin the Tag on the Monarch game.

Every year ANERR education specialist Lisa Bailey spends countless hours ensuring that Estuaries Day is a fun and educational experience for all who attended. However, she is the first to say that this event could not happen without the efforts of the entire ANERR and Coastal Office staff and volunteers. This year 30 staff along with 83 state employees and volunteers gave their time and energy to help make Estuaries Day 2018 the great success that it was.

Exploring the Bay’s Food Web

By Megan Lamb, Research Specialist

Anchovies have structures across their gill slits that send particles like copepods into their stomachs and not out their gills.

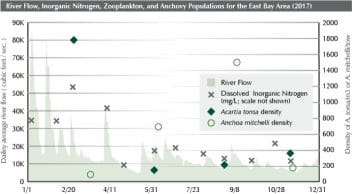

ANERR’s research staff conduct biological monitoring surveys in the Apalachicola Bay looking at parts of the estuary’s food web and linking the abiotic data collected by our System-Wide Monitoring Program (water quality and nutrients) to the biological food web. Staff conduct zooplankton and fish surveys four times a year at sites throughout the bay, from the nursery area of East Bay, near mud bottom habitats and oyster bars in the middle of the bay, to the grass flats and passes on the bayside between the barrier islands. This wide spatial sampling scheme allows us to determine if communities are not only present or absent in the bay at certain times of year, but also look at abundance of individual species and see if they move to different areas of the bay as water conditions change.

The zooplankton samples we collect are made up mostly of copepods. Copepods are small crustaceans that drift around in the water grazing on whatever they come across, including phytoplankton and detritus. Acartia tonsa is the most common copepod found in our Apalachicola Bay samples. This species is found in estuaries and coastal areas around the globe where high food concentrations are found thanks to high nutrient availability. Its single reddish eyespot makes this species, which grows to around 1.5 millimeter in length, very distinctive under the microscope. When we conduct our zooplankton sampling we do so in conjunction with our monthly long-term nutrient sampling program, so we can link the zooplankton community to the water quality conditions we see. Phytoplankton use nutrients, especially nitrogen, and light energy from the sun to produce carbon, and they are in turn eaten by zooplankton. In this way plankton form the base of the estuary’s food web.

The word plankton comes from the Greek root planktos meaning “drifter” or “wanderer.” Some plankton can swim, however they are at the mercy of the water’s tides and currents. Some species, like copepods, spend their life as part of the plankton, while others such as shellfish larvae spend only a part of their life cycle in the plankton before metamorphosing into their adult forms.

Calanoid copepods, including A. tonsa, are a favorite food the bay anchovy, Anchoa mitchilli. Anchovies have specialized structures across their gill slits called gill rakers -- long, thin projections that help send particles of a particular size -- like the copepods they want to eat, into their stomachs and not out their gills. These anchovies are especially abundant in low to medium salinity waters of 8-14 ppt (ANERR unpublished data), which is why they are often abundant at trawling sites in East Bay. The East Bay area is typically lower in salinities due to freshwater inputs from the river distributaries including the East River, St. Marks and Little St. Marks Rivers, runoff from the forest, and numerous creeks. Research by a former ANERR graduate research fellow, Dr. Jennifer Putland, showed that A. tonsa abundance peaks in summer in medium salinity waters (~14-22 ppt) (Putland and Iverson 2007). A. tonsa copepods are a favored food of bay anchovies (Sheridan 1978), so when these copepods are abundant, the anchovies will have a plentiful food supply. Using this information, Putland and Iverson (2007) predicted that reduced river flows in summer would reduce the areal extent of low salinity waters in the bay, in turn decreasing productivity and impacting the fisheries relying on these species. Lots of estuarine animals love to eat anchovies, including weakfish, striped bass, pickerel, bluefish, squid, ctenophores, terns, pelicans, and many more! Anchovies are considered critical to estuarine food webs because through their diet and predators, they link secondary production to higher trophic levels and fisheries outputs.

2017 Data from the USGS river flow gauge, ANERR’s nutrient sampling program, and phytoplankton and fisheries trawling program in East Bay. River flows are highest in spring, bringing nitrogen down river. Phytoplankton utilizes the nitrogen and flourishes, and ensuring copepods like Acartia tonsa have an abundant food supply. A. tonsa populations respond to the spring phytoplankton bloom, and anchovies A. mitchilli respond to the abundant food supply.

ANERR has been collecting fisheries data since 2000 and phytoplankton data since winter 2015. By linking these communities to our nutrient and water quality information, river flow information collected by USGS, we will be able to see how these communities change in species or abundance over time in response to varying conditions.

Moving from Grey to Green

By DJ Fontenot

A “rain garden” can concentrate and treat stormwater from other parts of the yard.

As Floridians, we are no strangers to storms. Their effects on our infrastructure are all too familiar:

downed powerlines, flooded streets, and washed out roads. As we look towards inevitable future storms, the decisions we make will not only be what we choose to rebuild, but how we choose to rebuild. This means exploring ways to make our towns and neighborhoods more resilient and sustainable through “green” infrastructure.

Grey infrastructure refers to traditional infrastructure and takes its name, mundanely, from the color of concrete that makes up so many of our sidewalks, pipes, and drains. Concrete is a durable, inexpensive, and waterproof material ideal for quickly moving water (i.e. runoff) from towns to the sea. There are, however, several disadvantages to high-speed water flows.

- First, just as we might safely wade across a lazy creek and not across whitewater rapids, fast-flowing runoff can carry much more litter and pollution into our bays and estuaries than slower runoff.

- Second, water flowing quickly from waterproof concrete can quickly erode natural earthen areas without vegetation.

- Third, stormwater is freshwater, which is vital for plants to thrive. Gray infrastructure doesn’t allow time for stormwater to seep into soil (infiltration) where our natural ecosystems and gardens might use it.

Green infrastructure, on the other hand, is a broad term that can refer to any structure or strategy that stores or treats storm runoff. As the name suggests, it often involves plant-based solutions. In a natural Florida environment, rain falls onto plants, slowly filters through the roots and soil, and eventually empties into bodies of water. The plants slow the water down and absorbs both water and nutrients that run off. Green infrastructure uses this idea of slowing and capturing storm runoff to manage stormwater in man-made environments like towns and neighborhoods.

Rain water may be captured in a barrel for future use.

For individual homeowners, the easiest places to install green infrastructure are yards. One simple example is rainwater collection. Home gutter systems typically concentrate rainwater into one fast flowing stream that empties into a yard or driveway when it could instead be captured in a barrel for future use. This solves both the problem of high-velocity runoff and of natural irrigation. In a relatively large yard that tends to retain water already, a “rain garden” can concentrate and treat stormwater from other parts of the yard. Rain gardens are made by forming a small depression that drains stormwater and filling that depression with attractive native plants that can handle sudden influxes of water. Unlike a retention pond, the water does not remain long after a rain event and will not promote mosquito breeding.

On the town or municipal scale, there are many ways to use green infrastructure to manage stormwater. For example, a “bioswale” is a strip of vegetation, usually placed along streets and parking lots, that catches stormwater, slowing it down and filtering pollutants before entering drains. Bioswales, like rain gardens, can use native shrubs and trees to treat water while also providing beautiful landscaping for citizens to enjoy.

Permeable pavement surfaces are another great way to capture and store stormwater. While normal concrete and asphalt surfaces are impervious to water, porous concrete, pavers, and gravel allow water to seep through instead of pool on top. Individuals can use these materials in driveways and sidewalks, and towns can use them for streets and parking lots.

While green infrastructure is not new, there is a growing realization we can get more out of what we build. Systems can be functional as well as beautiful, sustainable as well as affordable. The Environmental Protection Agency’s website is an excellent resource to learn more about the design, benefits, and even funding for green infrastructure in your towns and neighborhoods. The future will involve more storms and building green infrastructure is building with that future in mind.