Spring 2019

Spring is Here!

By Jennifer Harper, Reserve Manager

Just today, a co-worker commented about how green everything was now. But it isn’t just about trees budding and plants sprouting, it’s about regrowth following the hurricane where areas that were inundated with seawater are now coming back to life. It’s about much of the debris, whether it was natural or man-made, has been cleared from private property and our public lands. We are starting to see new construction, repairs to infrastructure, and restoration of our natural areas. All this is happening at the Reserve right now as well. We have ongoing repairs at the two buildings in Eastpoint and the Buffer Preserve in Port St. Joe. Our lands are slowly being cleared and re-opened for public use. Our tank systems are being re-engineered and renovations should start soon. We are hopeful that everything will be repaired and operational by summertime.

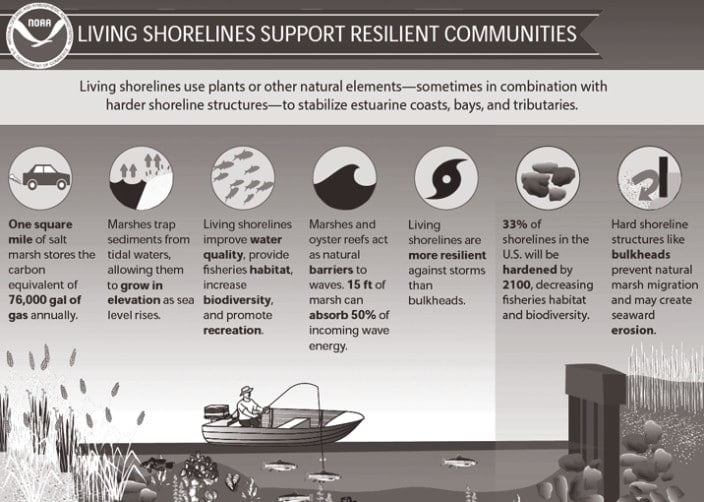

As all this is happening, one can’t help but think about how we can do things better next time (because most likely, there will be a next time). We certainly are making decisions about construction that consider what future conditions could be. Ultimately, we want to become more resilient by rebuilding in a way that results in reduced impacts and the ability to bounce back from events faster. In this edition of the Oystercatcher, Anita does an excellent job of defining resilience and what it means to us and our partners. Much of our efforts are focused on the built environment, but our natural surroundings need help too sometimes. Kim shares information about living shorelines, one method of reducing erosion and making a shoreline more resilient to storm events. Resilience is an important theme that we are focusing on as we conduct strategic planning for our new management plan.

Looking ahead to the summer and fall, we are also preparing for our 40th anniversary. The celebration will mostly take place in the Fall with Estuaries Day (September 27th) being the highlight. We are planning other special events, so please check our calendar for more information. We look forward to showcasing the valuable research, resource management, education and training that the Reserve has contributed to the area over the last 40 years.

Turtle Talk Tuesdays

By Gibby Conrad, Education Specialist

2 - 3pm, June - August

Summer 2019 marks the start of Tuesday Turtle Talks at the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve nature center in Eastpoint, FL. Turtle Talks are shifting from Wednesdays to Tuesdays this year to allow the Reserve Wednesday lecture series to continue through the summer months – plus the alliterative Tuesday Turtle Talks just sounds good. Please help us get the word out about the change.

Volunteers have always been an invaluable part of ANERR’s turtle patrols on St. George Island.

Volunteers have always been an invaluable part of ANERR’s turtle patrols on St. George Island.

Turtle Talks are held weekly from 2-3 in the afternoon June through August. The weekly schedule allows us to reach as many visitors as possible during the height of both turtle nesting season and the busy summer tourist season. It is not unusual for the Turtle Talks to draw 100 or more interested visitors who want to learn more about our nesting sea turtle population and how they can share the beaches with these magnificent animals while creating as little disturbance as possible.

Turtle Talks have been held at the Reserve Nature Center since the building opened in 2011. Prior to that, talks were given at various locations on St. George Island starting in 2000 when Bruce Drye took on the role as the marine turtle permit holder for St. George Island and volunteer coordinator. During his tenure from 2000 to 2015, Bruce witnessed the number of attendees at the talks rise from just a few in the early days to the much larger numbers that we are seeing today. Janice Becker took over the position in 2016 and has worked with the Education and Stewardship staff to revise and improve the Turtle Talk presentation to ensure that our summer visitors, which includes many children, are understanding their role in coexisting the with turtles.

The Turtle Talks grew out of the turtle beach patrols that started on Little St. George Island in the early 1990s. ANERR staff would patrol the beaches as part of their weekly duties on the island to mark nests and protect them from predation. ANERR staff are continuing to do all the turtle related work on Little St. George today. Since predation was not as much of a problem on St. George Island, more effort was put into lessening the impact of tourists on nesting and hatching turtles. Staff produced a handout for the realtors to give visitors with info on how to identify a crawl and who to contact about turtle related activities. Since artificial light disorientation became a growing issue as beachfront development increased, ANERR staff worked with the SGI Civic Club to get a lighting ordinance passed in Franklin County – one of the first in the state. Yellow lights were provided to beachfront properties to replace the problem white lights and Florida Power provided light switch covers to remind owners and visitors alike to turn off their beach facing lights during nesting season. When Bruce came onboard in 2000, beach patrols on St. George became more organized and grew into the daily turtle patrols that we have now.

Volunteers have always been an invaluable part of ANERR’s turtle patrols on St. George Island. Staff and volunteers now walk the beach from the state park to Bob Sikes Cut every morning just after sunrise. They mark and check the nests, record GPS coordinates and then monitor the nests through hatching. This is a monumental task that requires training and coordination of staff, interns and volunteers. There are now over thirty staff, interns and volunteers monitoring nesting activity on the two islands. 2016 and 2017 saw record numbers of nests with close to 800 nests between St. George and Little St. George. Last year’s numbers were down, but this was expected as nesting numbers tend to be cyclical. We will have to wait and see what 2019 brings.

If you are in the area June through August, please stop by for a Tuesday Turtle Talk. It will be a fun and educational experience.

What is Coastal Resilience?

By Anita Grove, CTP Coordinator

Enhancing Coastal Resilience is a goal of the Reserve

Hurricane Michael and the Limerock Wildfire are two recent reminders of our vulnerability to natural disasters. To prepare for future disasters, especially as they become more frequent due to climate change, the Reserve and its partners are focusing on resilience.

Resilience refers to the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems to sustain, adapt, recover, improve and grow, regardless of what kind of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience. Specific actions and implementation strategies are geared to address specific vulnerabilities (visit the 100 Resilient Cities website).

The National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration defines coastal resilience as the ability of a community to “bounce back” after events such as hurricanes, coastal storms, and flooding.

The National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) defines coastal resilience as the ability of a community to “bounce back” after events such as hurricanes, coastal storms, and flooding. When a coastal community is adequately informed and prepared for disasters, lives can be saved, properties spared, and natural ecosystems left intact. Enhancing coastal resilience is one of the listed goals at the Reserve, and is a priority for both NOAA, our federal partner, and for the Department of Environmental Protection, our state partner.

To assist our human and natural communities in becoming more resilient, Reserve staff works with the Floodplain Administrator for the Franklin County Planning office, the Franklin County Emergency Management staff, and the City of Apalachicola Planning staff and Planning and Zoning board members. We offer workshops and tools to help decision makers, residents and professionals assess and understand our vulnerabilities so that we can develop strategies to become more resilient to coastal flooding, storms and other disasters.

The Reserve has held workshops on FEMA’s Community Rating System (CRS) that allow communities to save on flood insurance by establishing policies that take advance protective measures and provide education in reducing exposure to flood dangers. We also hold regular workshops on protecting and strengthening natural infrastructure like living shorelines and other measures to reduce erosion. We partnered with the City of Apalachicola on a vulnerability study in 2017 and serve on the Franklin County Local Mitigation Strategy (LMS), a strategic plan that identifies ways to make the county more resilient to disasters. On April 11th at 4:00pm, we will host a workshop with Rod Scott on elevating homes and other structures to avoid flooding.

The Reserve partnered with the City of Apalachicola on a vulnerability study in 2017 and serves on the Franklin County Local Mitigation Strategy (LMS), a strategic plan that identifies ways to make the county more resilient to disasters.

NOAA offers several web-based tools to help communities understand and illustrate the effects of coastal flooding. On NOAA’s Digital Coast website coast.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/tools/coastalresilience you can link to FEMA National Flood Hazard Layer, a geospatial database and view other web-based tools. Reserve staff helped develop the Ecological Effects of Sea Level Rise, a dynamic storm surge and sea level rise model for the Gulf Coast from St. Marks to the Mississippi border. For more information, please visit the NOAA Office of Coastal Management website.

Resilience publications the Reserve has helped produce include:

- Florida Homeowners Handbook To Prepare For Natural Hazards, covers how to make your home safer and how to protect your property from multiple disasters.

- Coastal Resilience Index, a community self-assessment tool to help communities understand how prepared your community is for a disaster.

In February, our state partner changed its name from the Florida Coastal Office to the Office of Resilience and Coastal Protection. Part of our department’s mission now is to provide funding and technical expertise to aid communities so that they can become more resilient by integrating smart growth strategies into their land use planning to be better prepared for the next disaster. For more information, please visit the FDEP Florida Resilient Coastlines Program website.

Living Shorelines

By Kim Wren, Assistant Manager/Stewardship Coordinator

The Reserve’s focus is to restore, enhance and protect coastal resources

Living shorelines reduce coastal erosion by combining vegetated shoreline habitats with some form of living or natural breakwater such as oyster shells, limestone rock or other materials conducive to the natural environment. The combination of these features breaks up waves closer to shore, reducing wave energy as it comes ashore and then relying on native vegetation to absorb the remaining wave energy as water and waves encounter land. By maintaining a vegetated coastal edge with necessary tidal exchange, living shorelines preserve natural coastal processes that not only maintain coastal habitats, but can serve to protect and enhance nursery and critical feeding habitats for coastal and estuarine species. Living shorelines can also improve local water quality, reducing nitrogen and phosphorous loading in nearshore waters, by filtering run-off from upland areas and trapping nutrient rich soils in the shoreline system. Breakwater reefs serve as critical habitat for oysters. Juvenile oysters, or spat, latch on to the hard shells and/or limestone to survive. Oyster reef breakwaters improve water quality as each oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day. Living shorelines also provide scenic areas for recreation such as kayaking and bird watching.

A goal of the Apalachicola Reserve is to restore, enhance and protect coastal resources. The Reserve provides an ideal setting to investigate various approaches to restoring shorelines to near natural, unaltered conditions. Living shorelines have been demonstrated as a natural and effective technique to restore and protect eroding shorelines along the coast. Coastal communities face constant challenges from shoreline erosion. To test and demonstrate the effectiveness of living shoreline methods, the Reserve has installed six living shorelines over the past 20 years.

Over the last two and a half years, Reserve stewardship staff have worked closely with the Gulf Conservation Corps to construct two living shorelines within the bay consisting of bagged oyster shell and native vegetation. The Little St. George Island project consisted of a 400’ breakwater and native vegetation. It was completed in 2017 to protect the shoreline from erosion as well as the historic Marshall House on the island. The Sawyer Street project on St. George Island consists of a 250’ oyster shell breakwater and was completed in 2018. Native vegetation will be planted in the spring and a kayak launch area will be designated at the site. The team utilized shell that was locally donated. The Corps helped bag, transport and deploy well over 2,000 bags of material and 50 tons of fossilized dolomite. Restoring these shorelines will conserve and improve habitat and ecosystem function. Minor maintenance of the reefs will be necessary following Hurricane Michael in October 2018. These areas showed a decrease in erosion prior to the storm and the living shorelines prevented these areas from being significantly impacted during the storm.

Using a ‘softer’ or ‘greener’ approach to shoreline protection allows for a more natural aesthetic look in coastal areas and allows property owners or the public the potential to continue to have an entry point to coastal environments and waterways. Hardened shorelines produce a host of problems including loss of habitat for numerous marine species and wading birds, further erosion of the property that contains the structure as well as properties adjacent to the structure, water quality degradation and the interruption of natural shoreline processes (sediment transport). While hardened structures can be necessary in areas of high wave energy, they are too often seen in areas of moderate to low energy where non-hardened alternatives could be applied.

To learn more about living shorelines in Florida, please visit the Florida Living Shorelines website

Hurricane Michael Data Breakdown

By Emily Jackson

Some very unexpected things happened!

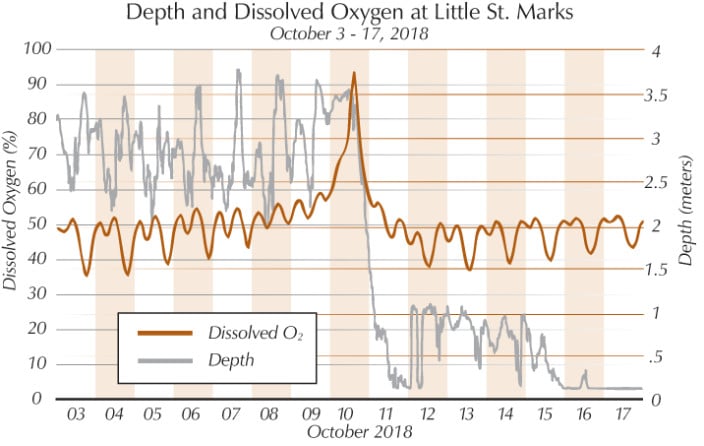

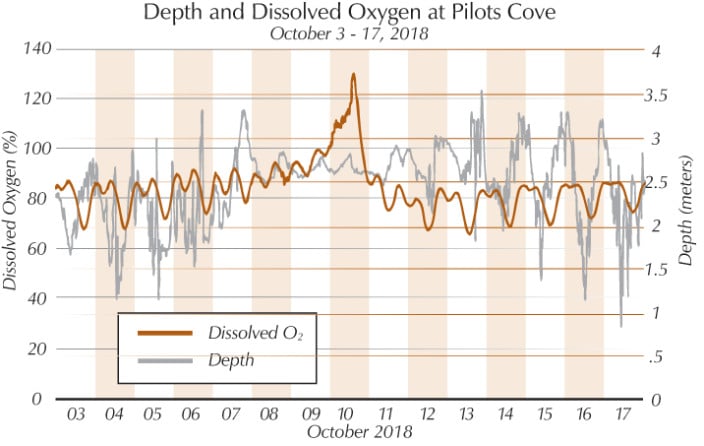

As one of the 29 facilities in the reserve system, the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve is tasked with monitoring water quality, weather, and biological factors like plankton and nutrients within the estuary. To do this we have established and work to maintain six stations throughout the bay with dataloggers that record water quality information every 15 minutes. While this data is useful for looking at long-term changes in the bay, it can also offer us an exclusive peek at the water quality during hurricanes – a time when it would otherwise be impossible to get on a boat and take measurements. With the information our dataloggers collected during Hurricane Michael, we start to see some very unexpected things happen with dissolved oxygen and depth between the river and bay.

Dissolved oxygen tells us how much O2 is available for fish to take from the water with their gills, and is usually measured as a percentage. Most estuary species do best in water with at least 30% dissolved oxygen. Keep in mind during the hurricane the pressure of the storm also pushes sea water up against the coastline, which floods our bay with storm surge and increases the depth. With a storm like Michael, we would expect to see both the depth and dissolved oxygen increased as storm surge came in and the wind and waves mixed more oxygen into the water.

At Pilot’s Cove we did start to see these trends. The Pilot’s Cove site is located on the backside on Little St. George Island, and was able to keep recording through the storm. Looking at the graph we can see the spike from the storm surge as depth increases, almost to 4 meters -which is 13 feet! The average depth for the Pilot’s Cove station in October is normally only 2.18 meters (7 feet). While the increased depth may seem dramatic, most of the organisms around Pilot’s Cove would be unaffected by the temporary change. The expected rise in dissolved oxygen around Pilot’s Cove is slower, but begins to occur early on October 7th, almost three days before the storm. As the weather kicks up before Hurricane Michael’s arrival, the mixing action at the surface is increasing, churning more oxygen into the water.

At the Little St. Marks station, located in the Little St. Marks River, these same changes occur at a slower rate. The impact on water quality that would be expected from the storm surge is delayed and weakened because the river is pushing back against the storm tide, filling the area with more normal water conditions until the last minute. The dissolved oxygen at Little St. Marks increases only by about ten percent leading up to the storm, and there are not significant changes in depth until October 9th and 10th, when Hurricane Michael arrives at the panhandle.

However, after the hurricane there is a dramatic and sudden drop in the dissolved oxygen at Little St Marks. Falling from 87% to 3% in a day, this sudden decline in oxygen would have caused stress to many of the species living in the river, and is most likely an impact resulting from the retreat of storm surge. After the sharp decline at Little St. Marks, the dissolved oxygen remains relatively low in the river area for several days. A high fish mortality around this time would be consistent, and expected based on the low oxygen conditions our dataloggers were recording. While we don’t have any nutrient or plankton data from this time period to say for certain, in the past powerful storms have stirred up the bottom, and resuspended bacteria and decomposing matter that quickly consumed the oxygen in the water. In areas like Little St. Marks, with lots of vegetation and minimal salt water, there is a thick layer of built up mud with lots of nutrients trapped underneath, and this makes the river more likely to be negatively impacted by resuspension. Our water quality data at Pilot’s Cove supports this; while the dissolved oxygen at Pilot’s Cove does experience a slight decline right after the storm, this area is primarily sand bottom, and contains less decomposing matter than the fluff mud in the river, so the dissolved oxygen here does not experience a steep decline after the storm surge leaves.

Overall, the water quality in the Apalachicola Bay returned to normal ranges within a few weeks of the storm. While severe weather events like Hurricane Michael may disrupt the normal water conditions for some time, the regular cycling of tides and river flow help to naturally flush the bay, and maintain the equilibrium that makes our estuary such a productive ecosystem.